description:

In the period 1700-1900, kings and empires rose and fell, but science conquered all, taking the world by storm. Yet, as the 1700s began, the mysteries of the universe were pondered by “natural philosophers”—the term “scientist” didn’t even exist until the mid 19th century—whose explanations couldn’t help but be influenced by the religious thought and political and social contexts that shaped their world.

episodes:

01. Science in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Professor Frederick Gregory begins the course by considering the special challenges facing anyone wishing to understand and learn from the natural sciences of the past, and introducing the major subjects and themes of the course.

02. Consolidating Newton's Achievement

This lecture explains how Newton’s theories were received by leading thinkers in France and Germany and describes the events that led to the eventual creation of a worldview that claimed Newton as its hero.

03. Theories of the Earth

Just as natural philosophers subjected the heavens to the rule of natural law over the course of the 18th century, so too did they scrutinize the Earth and its past with the same intent.

04. Grappling with Rock Formations

In the 18th century, the scope of German mineralogy expanded to include more than merely the mineral content of the Earth’s crust.

05. Alchemy under Pressure

The alchemical understanding concerning the interactions among various material substances was challenged in an attempt to define a rational approach to chemistry.

06. Lavoisier and the New French Chemistry

Investigators in Britain, Germany, and France sought to identify the properties of “airs” (gases) and to explore how they interact.

07. The Classification of Living Things

The view of living things that 18th-century natural philosophers inherited from their predecessors was challenged in this era.

08. How the Embryo Develops

How do embryos of different organisms, which seem in their earliest stages to resemble each other, know how and when to follow different paths to produce different adult forms? We examine the debate over embryonic development.

09. Medical Healers and Their Roles

This lecture examines the general understanding of health and disease of the 18th century as well as the bewildering array of medical healers that graced the countryside.

10. Mesmerism, Science, and the French Revolution

This lecture introduces the theories of Franz Anton Mesmer and details his sensational successes and failures and the reactions to his work, illustrating how natural science is not pursued in a political vacuum.

11. Explaining Electricity

Natural philosophers began to make real headway in explaining the bewildering phenomena associated with static electricity, with the mysterious force eventually capturing the attention not only of kings but of an astute American named Benjamin Franklin.

12. The Amazing Achievements of Galvani and Volt

This lecture examines—and clarifies—the work of the two famous Italian natural philosophers of the late Enlightenment as we look at their debate over the phenomenon of “animal electricity.”

13. Biology is Born

In the closing years of the 18th century, a fundamentally new view of life arises among natural philosophers, sharply differing with the conception of natural history that had come before.

14. Alternative Visions of Natural Science

The new outlook reflected in the science of biology was one marker of the end of the Enlightenment and the beginning of a new era, and we look at the differing visions offered by thinkers as diverse as Kant, Schelling, and Goethe.

15. Evolution French Style

During the first two decades of the 19th century, Cuvier’s position on natural history did not go unchallenged. Professor Gregory examines the objections raised by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, 25 years Cuvier’s senior, including their impact on his own career.

16. Evolution French Style

During the first two decades of the 19th century, Cuvier’s position on natural history did not go unchallenged. Professor Gregory examines the objections raised by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, 25 years Cuvier’s senior, including their impact on his own career.

17. The Catastrophist Synthesis

This lecture examines the unique route taken by the British to arrive at the controversy over life and its past that was already front and center on the continent.

18. Exploring the World

This lecture introduces the explorations of Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin and analyzes the significance of their journeys for the travelers themselves and for the natural science they influenced.

19. A Victorian Sensation

In 1844, the anonymous publication of The Vestiges of the Natural History of Creationtook Britain by storm, sparking debate that contributed to the tumultuous 1840s and helping establish the context in which the subject of evolution entered the British scene.

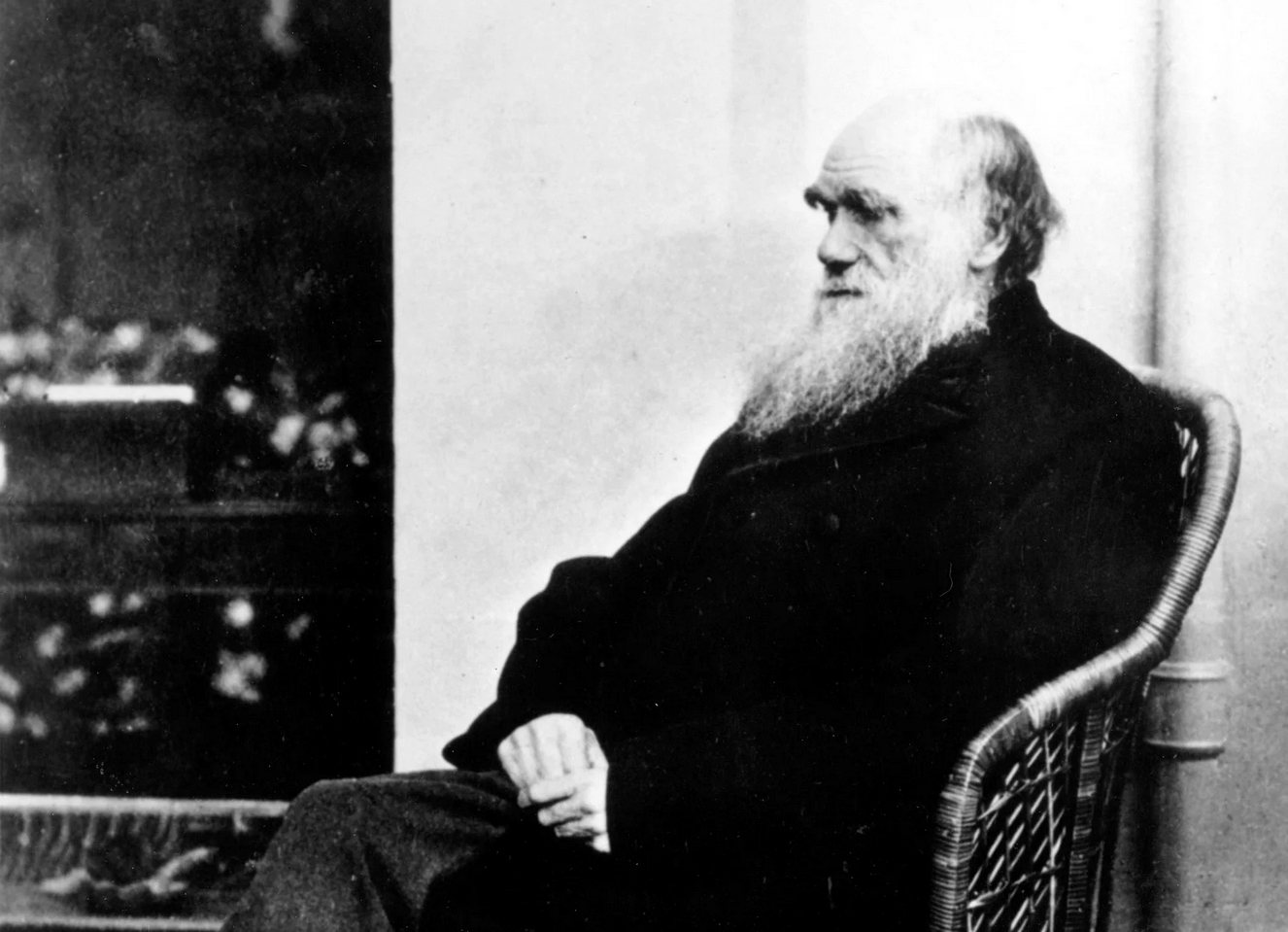

20. The Making of The Origin of Species

This lecture follows the path Darwin followed in creating and developing his theory in the years after his voyage, and in producing the hurried compendium we know as The Origin of Species.

21. Troubles with Darwin's Theory

During the first decade after the appearance of Darwin’s Origin, a number of scientific difficulties were raised by members of Britain’s now organized scientific community.

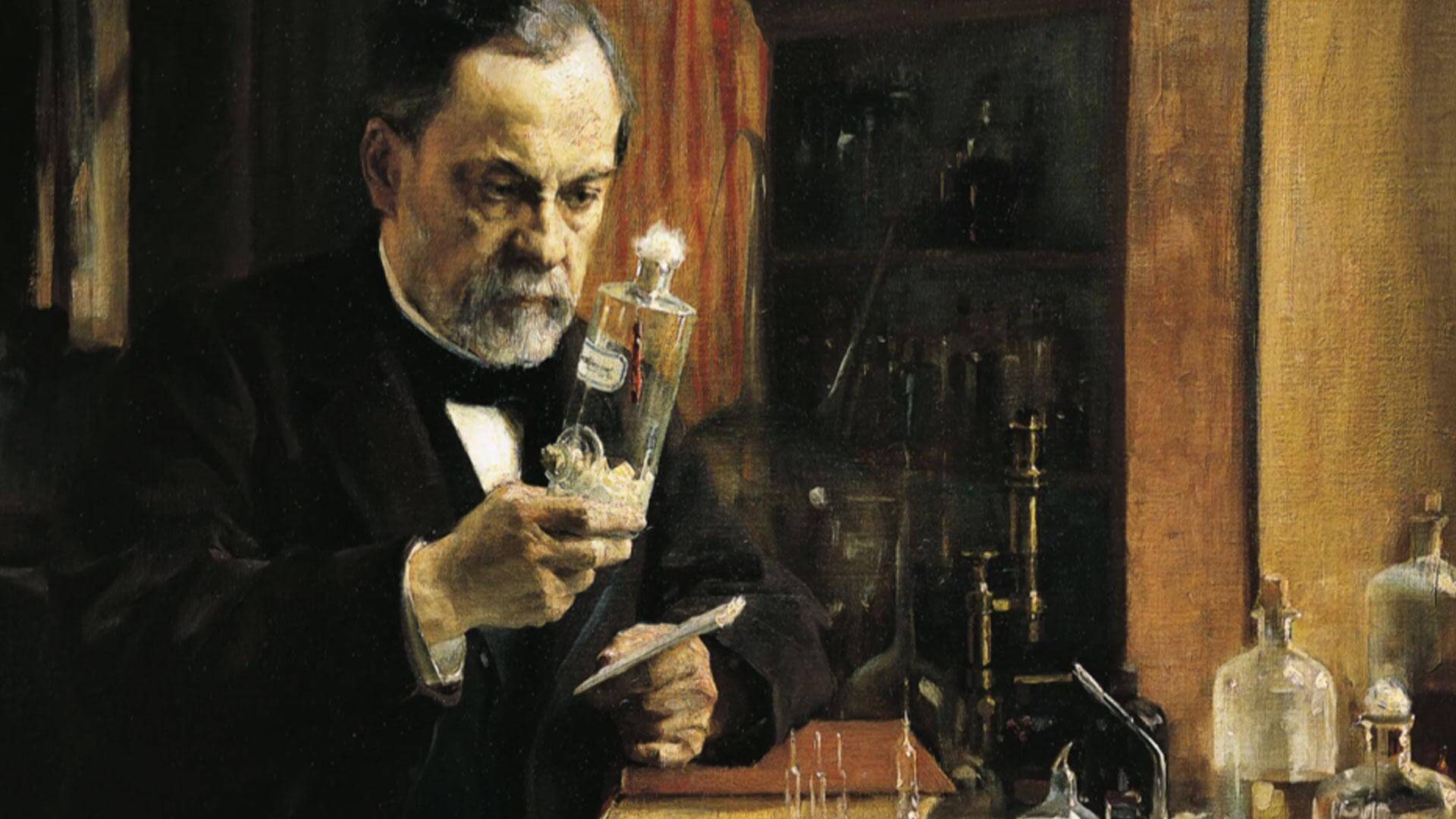

22. Science, Life, and Disease

As Darwin’s Origin appeared in England, another controversy—with religious and political implications—was brewing in France over the origin of life itself, with famous French chemist Louis Pasteur at its center.

23. Human Society and the Struggle for Existence

After the addition of Darwin’s Origin to the ongoing debate over evolution, the claim that humans should draw lessons about their own society from this new knowledge of the natural world was inevitable. But it was possible to derive very different ideas about what form that society should take.

24. Whither God?

This lecture examines the theological responses to the flourishing of evolutionary theory during the second half of the 19th century, which ranges from outright rejection to warm embrace.

25. Forces, Forces Everywhere

This lecture reviews the heritage of 17th- and early 18th-century treatments of motive force, primarily gravitation and the force created by collisions, and goes on to view the impact as natural philosophers uncovered new phenomena associated with heat, electricity, chemical change, magnetism, and light.

26. Electromagnetism Changes Everything

Danish natural philosopher Hans Christian Oersted uncovered the manner in which a magnet is affected by the flow of electric current, paving the way for later discoveries by Ampère and Faraday and the eventual creation of electrical machines that would directly affect society.

27. French Insights About Heat

Of all the forces of nature, it is the motive force of heat that proved to be one of the most intriguing during the early decades of the 19th century.

28. New Institutions of Natural Science

The emergence of a middle class public sphere and an increasingly significant role for something called “public opinion” paved the way for the emergence of the “scientist,” along with a wider concern for distinguishing natural science’s methodology.

29. The Conservation of What?

In the 1840s the continuing investigation of the interrelationships among nature’s forces leads to inquiries not only about the conversion of one kind of force into another but also about the possible creation and destruction of force.

30. Culture Wars and Thermodynamics

Continuing research into the back and forth interconversions between tensive and motive forces, especially when they involve heat, forced science and religion to seek a delicate balance.

31. Scientific Materialism at Mid-Century

This lecture examines a tumultuous period of conflict to which the addition of The Origin of Species in 1859 represented only more fuel to be added to an already raging fire.

32. The Mechanics of Molecules

This lecture returns to a survey of the knowledge of matter, picking up from discussions of the work of Lavoisier in Lecture 6.

33. Astronomical Achievement

This lecture examines the development of our views of the cosmos, including the nebular hypothesis of Pierre Simon Laplace and the role of a remarkable woman named Mary Somerville in translating and making his work accessible in Victorian Britain.

34. The Extra-Terrestrial Life Fiasco

The 1793 appearance of Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason ignited a raging debate over the compatibility of life on other worlds with the theology of Christianity.

35. Catching Up With Light

By the beginning of the 19th century, no consensus had yet emerged about what light might be, a situation that was changed by the establishment of a new wave theory and the work of Thomas Young in 1801 and James Maxwell at mid-century.

36. The End of Science?

This lecture examines the growth of the confident, and often overconfident, attitude that appeared among some scientists in the late 19th century, and concludes with two key developments that would challenge this confidence at its very core.

SIMILAR TITLES:

History of Science: Antiquity to 1700

History of Science: Antiquity to 1700

What Darwin Didn’t Know: The Modern Science of Evolution

What Darwin Didn’t Know: The Modern Science of Evolution

Understanding the Human Body: An Introduction to Anatomy and Physiology

Understanding the Human Body: An Introduction to Anatomy and Physiology

Big History, The Big Bang, Life on Earth and the Rise of Humanity

Big History, The Big Bang, Life on Earth and the Rise of Humanity

Science in the 20th Century: A Social-Intellectual Survey

Science in the 20th Century: A Social-Intellectual Survey

Great Scientific Ideas That Changed the World

Great Scientific Ideas That Changed the World